Don Quixote and The Enchanted Twenty-First Century

I finished Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes about a week ago. It took years to get through all 940 pages of this paperback Penguin classic, printed in 1952, with small type and thin pages.

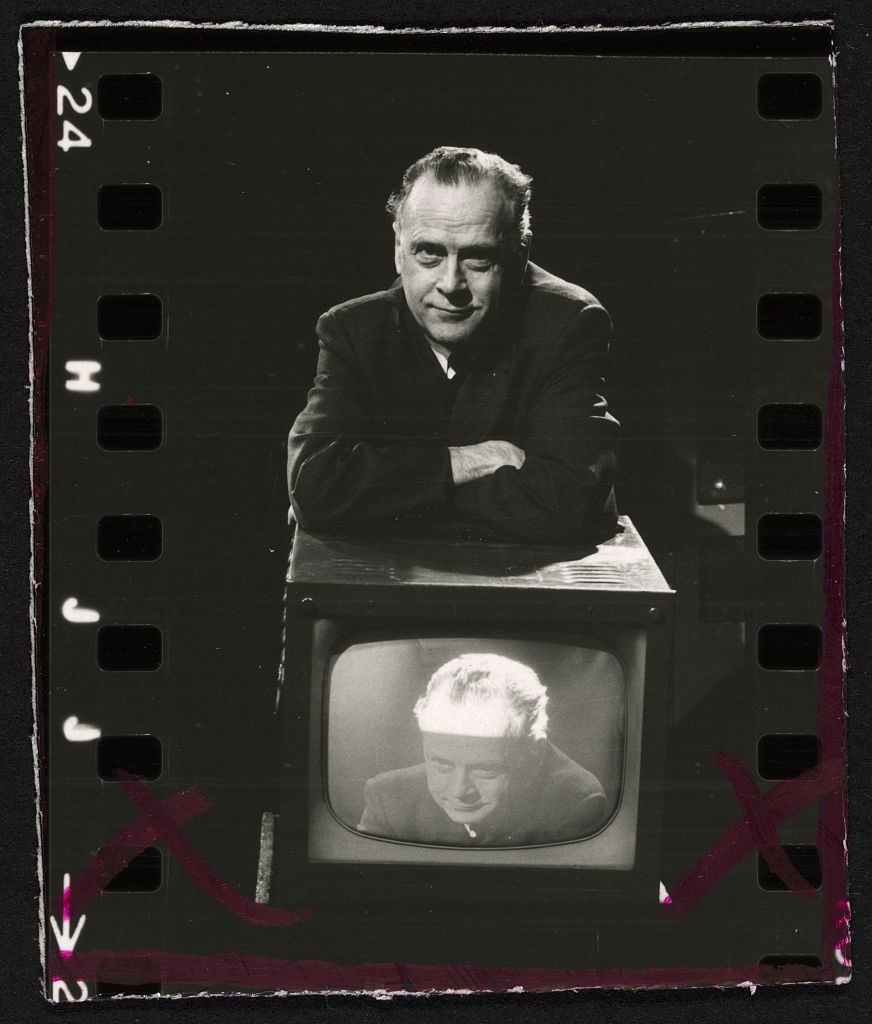

Something that prompted me to read it was Marshal McLuhan’s Understanding Media (1964). I picked that up at a used book store years ago because it is the follow up to his breakthrough work that I read over a decade ago, The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962), wherein he analyzed Don Quixote in the context of the onset of the Gutenberg era, after the invention of the mass printing press.

McLuhan regards the printed book as a low definition “cool” form of media, because it requires the reader to fill in the experience from their own imagination, as opposed to high definition “hot” media, which focuses your attention acutely, as in watching a film on the big screen. He describes a spectrum of media along these lines while discussing its corresponding medium, the technological continuum driving it. The printing press a medium that gives birth to an extraordinary range of media, now combined with electricity, there is an incredible evolution taking place in a rather short time span, and this greatly effects human evolution.

Cervantes’ epic tale was originally published in two parts, first in 1605, the second in 1615, each to about 400 pages. I would finish about 100 pages and then read another book, repeating the cycle until finishing Part 1. At least a year passed until I came to Part 2. I read that without interruption.

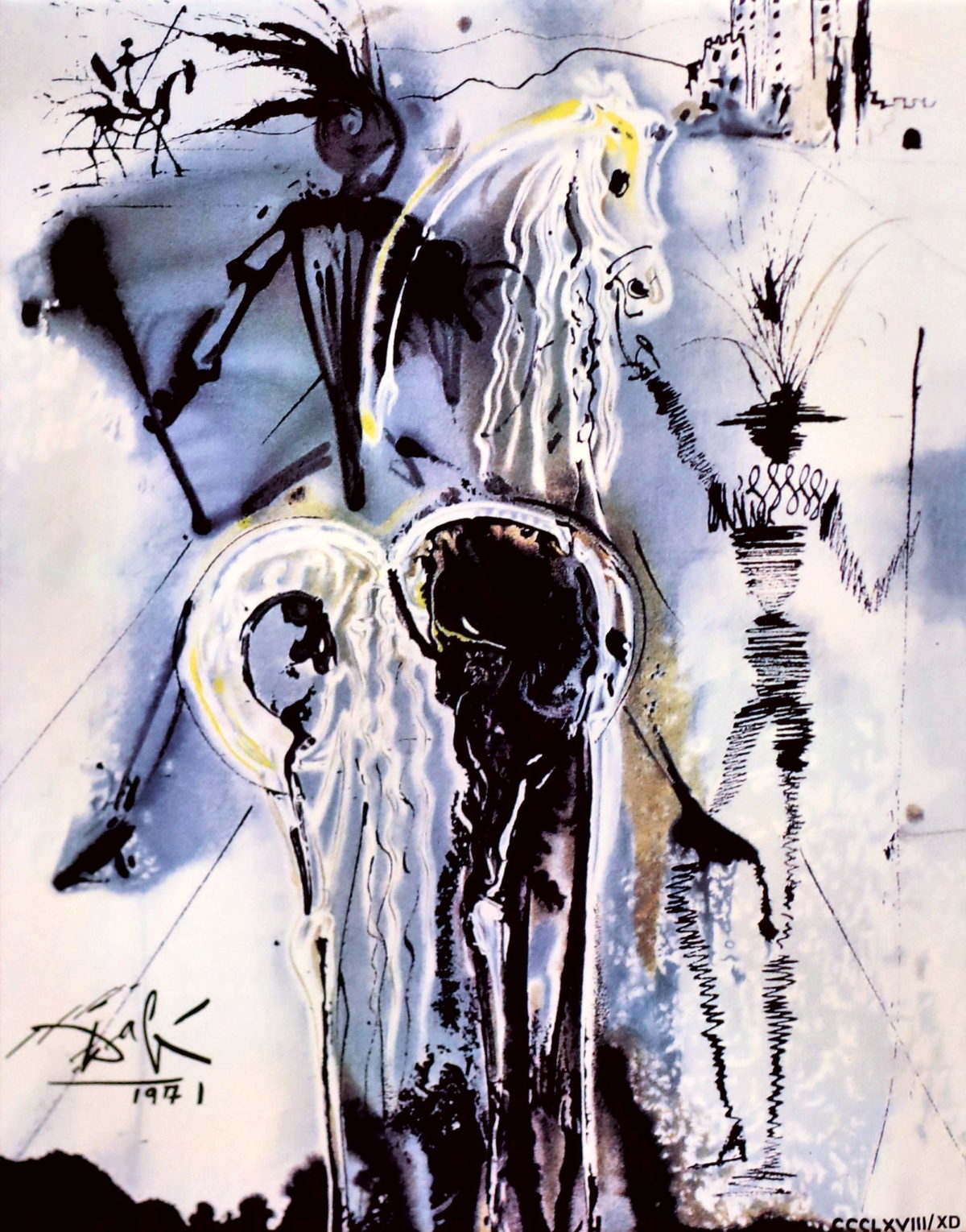

The story begins at the moment Don Quixote reaches the brink of madness. He is about to declare himself a knight errant. This role that he desires is entirely informed by books of chivalry — epic tales of medieval knights — contemporary to Cervantes’ time. The knight errant serves no royalty directly, instead, they roam the world like superheroes, doing what is right by the natural order of God’s creation, in a strictly Catholic Christian sense.

Quixote is a Spanish property owner, regarded well in his village, a man of fair means and educated, but he is spell bound by these books which were made to appear like historic documents when they were in fact fiction. His friends see through it but they cannot persuade him otherwise because the man is extremely clever, and hard-headed.

Quixote, the self-ordained knight, takes his friend, the illiterate Sancho Panza, as his squire. Sancho is a much simpler man but he is above the servant class. He is married with a daughter, he is a property owner, but he cannot read. He is oriented in the way that McLuhan calls audile-tactile. He hears and he feels above all.

Sancho excessively strings together proverbs, an oral tradition (also a kind of media), rather than drawing up his own words, almost like he’s building his perspective with bricks. This annoys Quixote all the time, who is visually oriented because he is literate, and excessively so because he has time for leisure. His imagination is developed enough to dream a new identity for himself, and his intellect is developed enough to rationalize it.

No sooner do they set out on their journey does Quixote act as if he’s been a knight his entire life. He’s unshakeable from his vision. He hallucinates inns for castles, sheep for soldiers, most famously windmills for giants, and much more.

Quixote promises Sancho the governorship of an island when they are through with their conquests. This one fantasy is enough for Sancho to overlook all of his master’s red flags. He manages the delusion, as often as possible toward his own benefit. Not that he isn’t loyal, he never stops believing in his master’s powers and intellect.

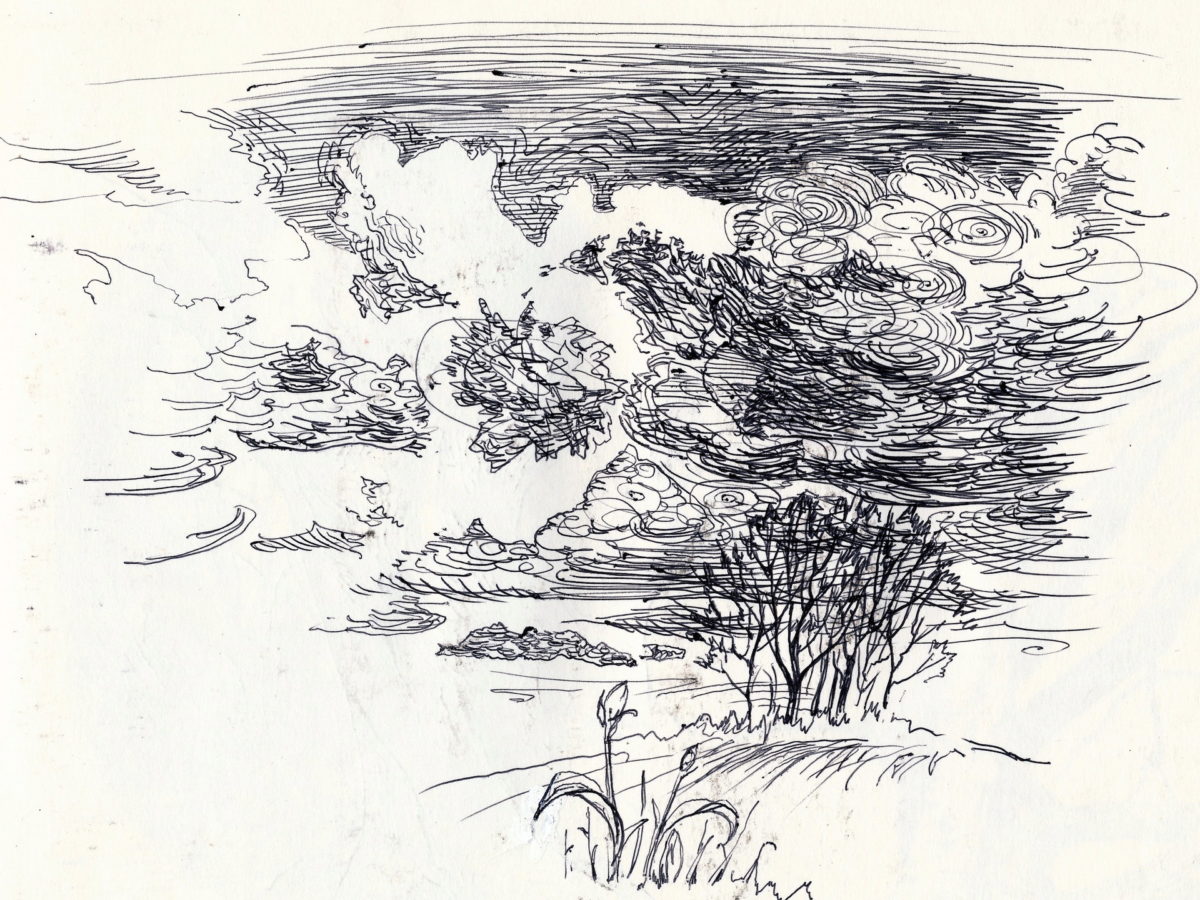

This premise is potent enough to put the duo into a variety of hilarious situations that amounts to a whole lot of slapstick humor, bold wit and philosophical discussion that would be hip for the time. It’s also psychedelic, if you can only imagine the hallucinations that Quixote must be going through. I wish Alejandro Jodorowsky would make Don Quixote into an epic film.

McLuhan predicted in the middle of the twentieth century that human beings were on the way to adapting back into an audile-tactile orientation just at the peak of the visual-literate era.

He sees the burgeoning world of television, radio, and printed audio as an extension of the Gutenberg press. Vinyl records, magnetic tape, film, mp3 files, DVD’s, it’s all the same, in essence. It’s just accelerated by the revolution of electricity, introduced en masse in the early 20th Century. Broadcasting is a major leap in delivery, as electricity naturally wants to network itself into channels, and we have such granular modulation of electric current that we can generate infinite signal channels and nodes.

Starting around the 1920’s, every household was to possess electricity, then a radio, then a television, eventually a computer, and now a network of computers inside televisions networked by wireless radio signals in every room of the house. Multimedia was a new concept 100 years ago, now it’s ubiquitous, and we’re all producing it.

The internet is the complete realization of electrical networking, it accelerates the production and delivery of media, and this new accelerant delivers a quixotic effect on the people because it replicates reality like a hallucination. The internet is still driven by text, but that will gradually give way to more audile-tactile content like interactive virtual spaces. I don’t believe we have a media hotter than virtual reality.

Quixotic is a literal description of the character Don Quixote. It is the state of being unpredictable, impulsive, impractical, and a touch mad. It is a precarious state of mind. I have lived a precarious life full of weird situations brought about by my quixotic personality. I was raised in some ways by media. My parents worked hard and I found myself highly influenced by television, video games, music, and as I got older, film and books.

Today, children are graduating public high schools illiterate in the worst cases, unable to read traditional clocks and solve math equations in too many cases, and yet they have mastered the audile-tactile universe of the smart phone and computer technology; they are highly socialized and have developed a sophisticated oral tradition of slang not unlike proverbs, more concise and granular, but shorter in attention span as new slang doesn’t convey complex ideas and principles, it’s more about feeling.

I believe that the illiterate kids entering adult life today are most persuaded by the promises made by the highly literate, who are most capable of persuasion, by the promise of instant wealth, fame, and grandeur, conveyed in the form of audile-tactile media.

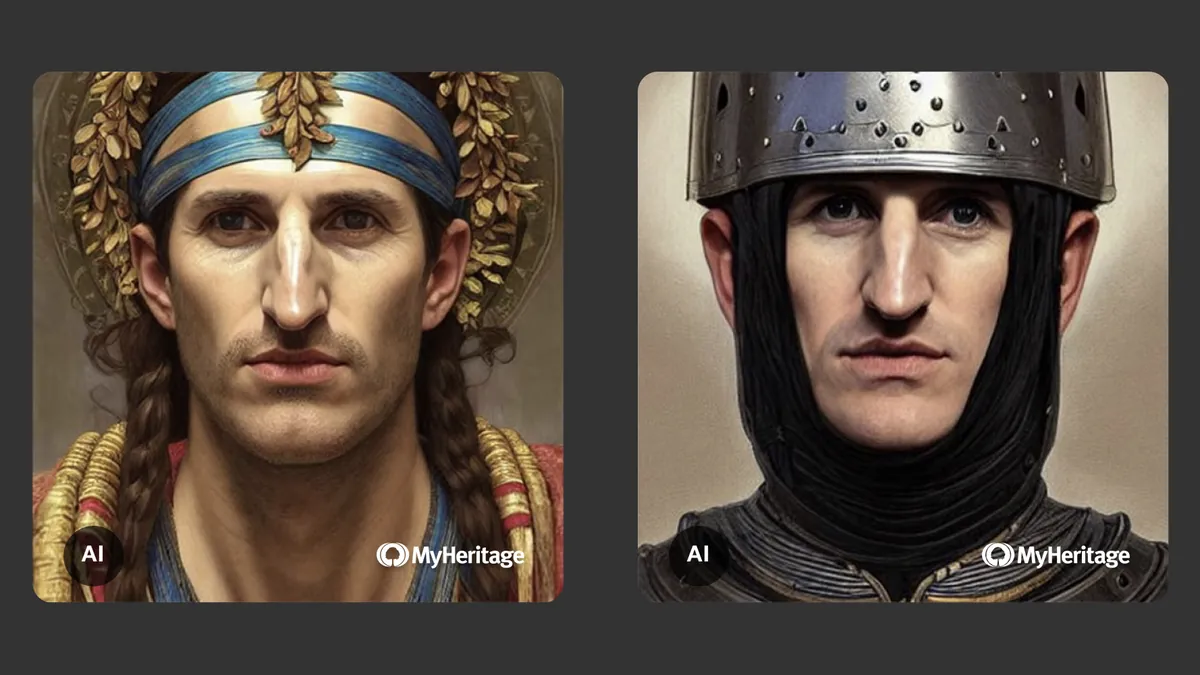

The universe inside the smart phone, accelerated by new so-called AI technology, is quite literally transforming people into knights, dames, wizards, and all manner of mythical characters, and people are posting AI generated pictures in their profiles as if it was a recent portrait.

It could not be more obvious that McLuhan and Cervantes were right, that we are becoming Don Quixote or Sancho Panza, or both. If we don’t become zealous self-led identities, we are led by them, or we alternate both patterns.

The class of people that run the machine is different from those consuming its content. They know the power they wield while most of us don’t understand the influence we’re under.

By the end of Part 1, Quixote and Sancho have been battered, bruised, starved, and humiliated before they are dragged home by their village friends by hook and by crook. Quixote cannot accept that he’s going against the grain of the world while neglecting his real life, to him, he is under an invisible siege of enchanters, that there are wizards and demons sabotaging his heroic efforts, causing his hallucinations and follies. Sancho just keeps going along with it, seduced by the promise of governing an island.

For the second part of the book, the duo is infamous. The story of their follies got around by word of mouth, until a book about him and Sancho was published unbeknownst to them.

They had become a meme.

This time they were being deliberately tricked into situations by people who read the book, including a Duke and Duchess.

In a way, it is a fake it until you make it kind of story, for his reputation precedes him and eventually Quixote is treated like a knight, and he eats it up. Sancho becomes a governor just like he was promised, appointed by the Duke.

The problem is that in reality, they are pawns in a conspiracy largely devised for the amusement of a powerful couple. They actually persuade Sancho that some of what he witnessed really was enchantment.

The thing is, that when your ego is all wrapped up in the cloak of identity, and seduced by desire, it is highly susceptible to manipulation.

What is frightening to me is that technology has caught up to the human brain. Beyond the dopamine hits provided with endless rotation on social media, which is enough to control someone’s thinking, it is reportedly possible to send and receive thoughts and feelings into individuals. The technology is being tested surely on both willing and unwilling participants.

My upbringing was unusual and social integration has always been difficult for me, so I believe that my identity suffered a substantial number of schisms, enough to make me a rather irrational, impulsive, dreamy, desperate young man.

Quixote believes that he is enchanted, but my equivalent to feeling enchanted is tied to our paradigm of surveillance and controlled opposition. That paranoia enlivens sometimes, and I don’t know if I’m wrong, because I consume media that depicts a world of conspiracy. Anyone can become a target of the powerful, especially those who stick their neck out. Not to get into details, but I’ve been set up, coerced, investigated, and surveilled, at one time or another in my life, and sometimes you have no idea it’s happening until it’s done.

All in all, my life has worked out remarkably well, as I think I’ve taken more risks with people and situations than I should have survived through. Honestly, I believe when we deviate from our true purpose to fulfill a self-identity, shit gets weird, we become vulnerable.

I cannot allow the ego to build my sense of purpose, rather it is ordained and determined by the authentic people in my life delivered by karma, which I believe is the medium of God’s grace and mercy, for I have rejected her guidance excessively out of ignorance and craving.

We do not all have a grand purpose in life. We cannot all be spectacles, and frankly that’s a difficult fate most people cannot handle.

Quixote’s ego got the best of him. Call it a mid-life crisis, his humble purpose and responsibilities must have felt droll and lacking inspiration. He is alone, apparently never married, no children, and he cares for his niece and one house maid. I think he was bored, and sad. In fact, he declares himself the Knight of the Sad Countenance at the beginning.

He dedicates his new life to Teresa Del Toboso, a woman in the neighboring village that he claims is the fairest, most virtuous, and beautiful woman on the planet. It is revealed however that he only saw her once, and never met her. It’s like a crush gone too far.

Now I can relate to that. I’ll get myself crushing on a girl and in my mind we’re already together. After my sex magic episode of The Not-a-Podcast Show, I realized that the subconscious is easily persuaded by our imagination, as in the context of masturbating to a crush that isn’t reciprocating. Vastly more times than not, I end up crushed, because I became attached to my crush as if it were a real thing.

So long as mass media is constantly showing us a world of sex, glamour, wealth, and exoticism, some people are going to live with the anxiety that their lives don’t measure up, and will act on it, one way or another, self-destructively.

Impatience under the lure of self-image results in putting the cart before the horse.

As a young adult, I declared myself a musician before I had developed my musicianship. In my early thirties, I declared myself a journalist and publisher before really understanding what is entailed in starting up a magazine. I did all kinds of silly things that nobody asked for. It does not characterize my whole life, but it’s enough to see aspects of my story inside Quixote’s.

People did respect the man’s valor, for he was fearless, and survived his follies with endless determination. That kind of infamy however is much different than his self-image, and that delusion is pathetic.

Quixote would be able to speak intelligently and at length on all kinds of subjects, but he could so quickly drift from clarity and poignancy to utter nonsense derived from hallucinations and false books. I can relate to that. Consistency in thought was not my thing, rather just the ability to think and speak with confidence whilst patching logical holes on the fly, I was persuasive, and at the least people were entertained.

All I look for now, in myself and others, is consistency in thought and deed, because the compartmentalized person is not a whole person, and they can easily move you to the shit box.

Quixote was so hard-headed, you dare not contradict and challenge his profession, for he might challenge you to a dual. That was me, and that is anyone whose identity has been constructed in this way.

Around page 700, there are signs that Quixote’s wits are coming back, as his hallucinations start to go away, around the time that he is recognized by the public as a knight. It’s like he could not live in reality until reality conformed to him. By the end, he recognizes his error, but the damage is done.

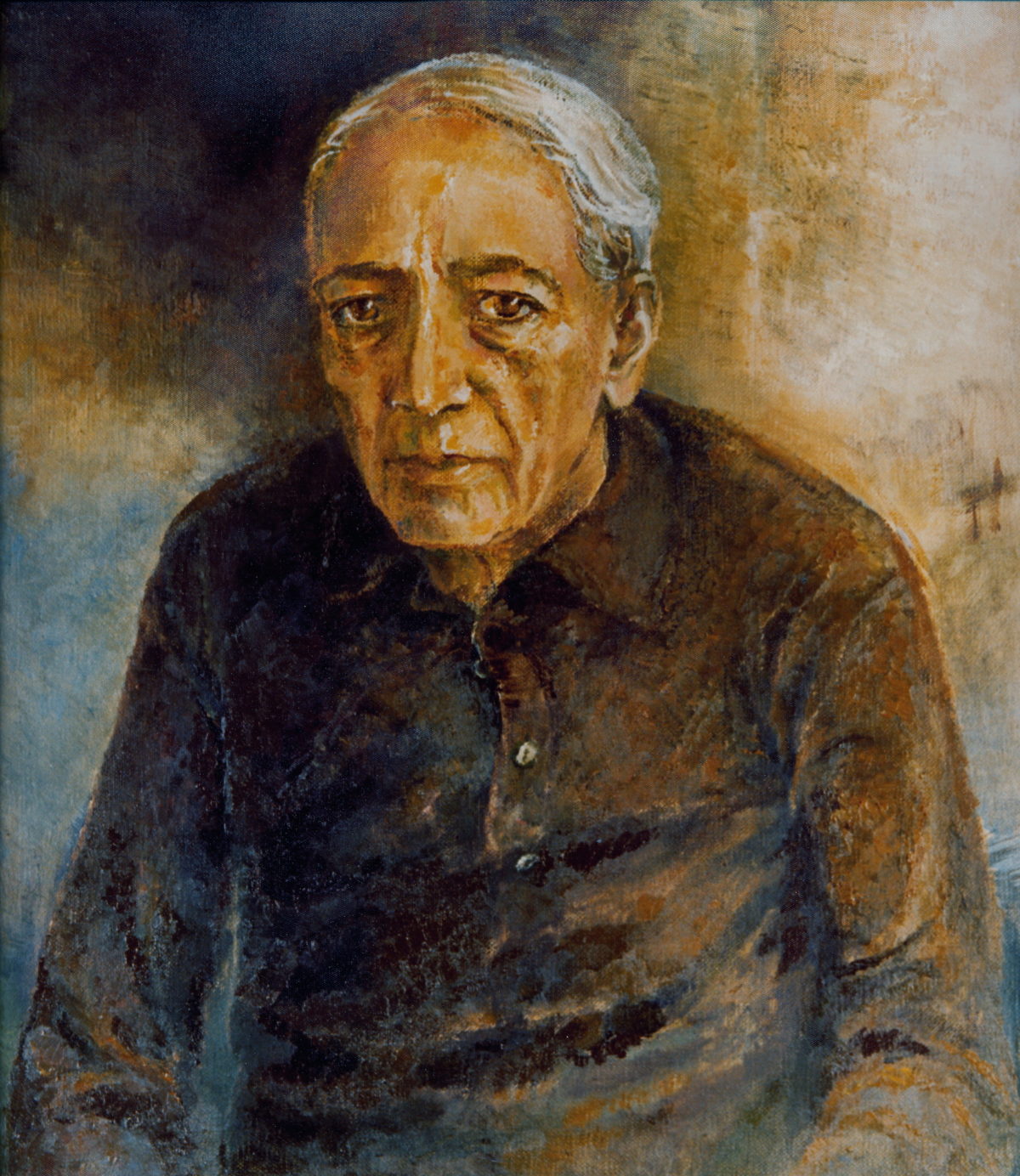

After twenty years of exposure to Jiddu Krishnamurti telling me that only when we die to knowledge can we be liberated from its conditioning, that the accumulation of knowledge as dangerous, it took reading a classic story for me to see that point fully.

Like our possessions, the identity cannot be taken to the grave. Our identity is the accumulation of knowledge applied to time. In the end, it is left in the hands of those who witnessed our deeds. There is no true self outside the memory of our witnesses.

When we are young, we go through the stage of exploring the “true self” and we search it out. The hazard is that it can be corrupted and made grotesque by the images that we put on ourselves, usually influenced by media. The humbling fact of our mortal existence and the abyssal emptiness of our true self can be too much to bear, so we use self images to feel permanent.

If we see a sexy someone that turns us on, or a lovely piece of clothing, images of exotic places, bawlers throwing Benjamins around, or anything in media that draws our attention away from the painful truth of immediate existence — our loneliness, our ugliness, our internal or external poverty, our monotonies — it gives us a projection to live within, to aspire to become over time. We spend most of our lives in this conflict between our immediate selves and who we want to become in the future. The problem is there is no future, just endless immediacy.

It is a natural youthful and maybe necessary thing to invent a true self to become, but it’s a sad thing to see an older man whose life is already laid out before him, whose responsibilities are already clear.

The scary thing is that I’m 40 and I’m not positive if I’ve changed. Whenever I think I have, I repeat a cycle, then peel back the onion and wonder if there is an end to ego at all.

Today, we see a lot of film and television characters of grown up children, which I think is a real outcome of the trauma of hyper exposure to multimedia.

Entering the second part of my life, I am more focused on process than outcome, I ask God for my purpose and I watch the universe respond to my efforts to discover it, because if I’m running into constant conflict like Quixote, then surely I’m deviating.

There must be a balance between imposter syndrome and healthy self-awareness. Quixote would have benefitted from a little imposter syndrome, as he was in fact an imposter. It’s one thing to be perseverant, disciplined, it’s another to be oblivious to yourself.

Rarely does the world bless us with a true visionary, someone that sees the truth unfolding in real time, someone that perceives on a higher level. Quixote is the invention of a visionary, Cervantes, to illustrate self-deception.

Maybe we all can access truth, but I see now it can only happen by liberating ourselves from deception, and deception starts with the self.